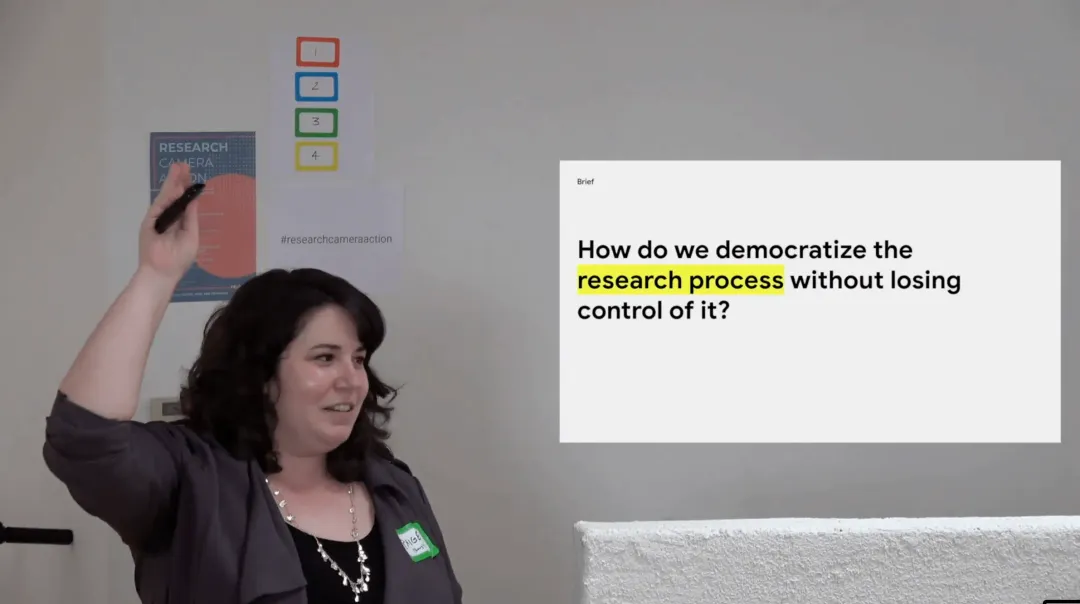

Democratizing the research process without losing control

September 2021

·

9 min read

Democratized research practices vary: from getting non-research stakeholders involved in research, training non-researchers to take on specific kinds of research projects, to opening up the gates entirely for anyone to do research. Regardless of the approach, there are some core points of friction that almost always come up.

In this article, we cover three major points of friction that Paige Pritchard saw and overcame at Google. Paige draws on her experience in two different roles: as a horizontal researcher in the Rapid Research Team and as an embedded researcher on a new product ("Fuchsia"). In addition, given that not every organization can operate at Google scale, we also include similar approaches and lessons from teams at Dropbox, Stripe, Gusto, and Scoop.

Before we dive in, it's worth describing the Rapid Research Team at Google, which has a very unique model of user research. The Rapid Research Team is a horizontal team designed to turn around very quick research projects: usability studies, literature reviews, and popup research in just _ one week _. The team often partnered with embedded UX researchers to help increase their bandwidth around particular studies, and was in charge of a particularly interesting research tool - the Google Van. This van allowed teams (UX researchers, designers, PMs, and even engineers) to go out to places outside of the tech bubble to obtain rapid fire insights.

It was driving this research van that Paige came across the points of friction that challenge any democratized research practice.

Tension #1: Is a researcher an expert or a facilitator?

Every researcher struggles with finding the balance between advancing the larger research strategy ("following the north star") , and helping teammates perform their own scrappy and tactical research.

For instance, a UX Researcher working on Google News might have a research strategy focused on understanding what credibility looks like when it comes to news media, the north star of the Google News product. One week, a designer on the team might have an idea to label a media outlet differently in a way that resonates with this overall research. And they want to study whether or not it makes an impact on end users. This week.

How does the researcher balance the two needs?

At a scale like Google's, a horizontal team like the Rapid Research Team can provide a great solution to this. This team's goal is to buttress embedded researchers, and do the tactical research that needs to be finished quickly. This allows the embedded researcher(s) to continue to focus on their north star research strategy. They can focus on larger scale studies to get at deeper questions, while the horizontal team comes in and conducts usability studies to provide teams with quick insights. Researchers here are in "expert" mode.

The alternative solution is often to create the infrastructure for designers to do their own research. For instance, during the early days of Fuchsia, the researchers would book a conference room every month, recruit users and tell the designers to show up with some mocks and talk to users about it. A brief sync between the researchers and designer would follow, where the researchers and designers sat on the same table to make sense of the data they collected. To put it another way, the researchers are in a "facilitator" role, allowing non-researchers to do their own research but still being available to help with the process.

Both models can be effective, and lend themselves to different contexts. "Expert" mode tends to work best for strategic, in-depth, and high context research that's often foundational or generative in nature. "Facilitator" mode is great for supporting tactical studies that can allow teams to keep moving at a fast pace, and allow design to have at a much larger scale.

Some teams make an explicit gradient incorporating these trade-offs. At Dropbox, the historical model of research was very much researchers working as "experts." But in recent years, as the demand for research has grown, some researchers have taken the explicit role of supporting a democratized practice. To do this, they have taken a three-pronged approach. First, they allow any team to conduct unmoderated remote research on their own. Second, they host "Real World Wednesdays," where users & teammates are invited into speed-dating style research sessions to concepts in short (15 minute) moderated sessions. And third, the democratized research practitioners provide hand-on support (almost as in-house consultants) to teammates wanting to do more complex research, helping ensure that they are well supported in everything from recruiting, to study design, to ethical and privacy considerations.

Tension #2: Who owns what? Gatekeeping vs. Ensuring Quality

Figuring out just who has access to what tools and who makes what calls when it comes to research is one of the biggest challenges for research teams. At companies like Google, where you're surrounded by the best UX practitioners in the world, even a UX designer or a UX engineer has some background and training in research. They want to be involved and that is a good problem to have, but it can lead to having too many cooks in the kitchen.

For example, Paige had an experience where a designer wrote a big multi-page research plan and sent it out to team leads and PMs before she even got a chance to look at it. After review, she had to find a way to reel it back and say, "No, actually let's focus on something else," without stepping on anyone's toes.

That is part of the reason why at larger organizations like Google, tools are restricted to certain roles. Only researchers can do the recruiting, only researchers can book the research van and drive it. This can come as a surprise to people who have come from another organization where they had all the access to different tools.

A legitimate concern from non-researchers is that the process might be bottlenecked if they always have to go through a researcher to book the labs to do a study, but Paige advocates that in a large organization like Google, non-researchers should think of these limitations as more of a guiding principle than a bottleneck, while also acknowledging that while this works at Google, this approach could be a bottleneck in other types of teams.

More specifically, Paige has addressed this friction as a researcher by clearly defining within her team what needs research approval and what non-researchers can do on their own. For instance, when the designer went off and made their own research plan, Paige wasn't upset. It was great engagement to have designers thinking about research, as long as there are avenues for guidance from researchers.

Fostering this engagement while providing guidance requires a delicate balance. The last thing you want is for your team to be anxious, thinking "Oh, do we need permission?" for every single idea. For Paige, the solution was to sit down with her team and define the boundaries. For example, if they wanted to design a practicum of research with multiple studies involved, they should definitely loop a researcher in, as their input will be critical to make such complex projects successful. But if her team wanted to print out some mocks and test it with people internally on the team, no consultation was necessary.

Another part of the solution is to create a research archive, and train people within the team to use it, so that they can build on top of existing research on any topic. For instance, if someone has a question about notifications, chances are that there has been a research project already conducted on the topic. Training people to use existing archives of research on their own can be an extremely high leverage methodology for democratized research.

Want to build a searchable archive of all the user research video in your organization? Get a Free Trial

Gusto employs a similar solution to keep a little bit of control on the chaos. A lot of the design team and PMs at Gusto do their own research - and in fact come into the job knowing that they'll be doing research as part of their work. Gusto researchers don't want to be the bottlenecks, but do need some checks in place on who they contact, or what rooms and tools they are able to access, etc.

So the Gusto Research Operations team has created an open-door policy where the designers and PMs can ask for assistance or advice at any time. The ops team then takes notes about upcoming research, and are able to check in on them without having to be the bottleneck. The research ops team provides some additional assistance (eg. providing tool exposure and training) when they're involved, providing an incentive for non-researchers to utilize them. This way, they are able to maintain high visibility on ongoing research, without becoming a bottleneck in the process.

At Stripe, the level of involvement is dependent on the methodology and tools being used. While the team generally operates without bottlenecks, they made an exception for Qualtrics (the survey tool). For qualtrics, the research team maintains control and the whole process is set up to make sure that the researchers see everything before it goes out the door. The message to non-researchers at Stripe is that while they are generally empowered to conduct their own research, some tools & contexts require specialized knowledge, and need to remain under researchers' control. With surveys, for example, anyone can easily send out thousands of surveys, so the potential to cause errors (and potentially even cause damage to the brand) by using those tools is significant.

Tension #3: If everyone's able to do their own research, why do we even need a researcher?

For Paige, the idea that researchers will democratize themselves out of a job is less of a problem that she's run into and more of an anxiety that she's felt in the industry. Unfortunately, it's an idea that permeates.

If researchers teach everyone to do their own research, will they negate the need for their own position? How will researchers make the business case for increasing the headcount for their team or increasing the research budget, if they aren't able to protect their own role? These questions weigh in on every research team's anxiety when they're considering the pros and cons of democratizing research.

Paige's solution is to approach this with the right mindset and use the expert facilitator idea for her benefit. The tone from the research team should be "Yes, you can do research, but I am the person to come to for the expertise on it." This goes both ways, a designer can run a research study and bring back the findings to the researcher, just as the researcher is free to sketch out a wireframe and go to the designer with ideas to improve the flow.

This sort of dabbling in design by the researcher doesn't negate the role of the designer and neither does the designer doing a bit of research negate the role of the researcher.

The research team at Scoop had similar anxieties when they designed a "research menu", a list of all the methods that they use, definitions, the value of each method, and the timeline of how long they usually take. When they distributed this within the company, there was some anxiety that the response would be "Okay, [now] you guys are unnecessary. I can totally take this on." But the reality was very different. The research menu actually gave the team a richer understanding of research. So they could now map their problems to how the research team would help them — "Oh, this is fabulous because this is the problem I have and you're telling me this is exactly how you can find a solution or look into it more."

By outlining what research is and by investing on the UX infrastructure to make sure everybody in the company can see what the research team is doing, research teams don't negate their roles. In fact, they help the company understand the rigor and depth that goes into research. Instead of saying "Let's do a study within a week," stakeholders start collaborating with researchers with more realistic expectations about the timeline of a research study, including recruitment, booking rooms, leaving time for synthesis, and other constraints & steps that non-researchers might not be aware of.

Reflection: Embracing the confidence of being a researcher

While these tensions are real, they can be managed. As we see from democratized research practices from Google, Dropbox, Stripe, Gusto, and Scoop, there can in fact be many different approaches to managing these tensions.

One common theme that we see here at Reduct is that success in democratizing research goes hand in hand with embracing the confidence of being a researcher. Democratization doesn't mean that all research is democratized — there are cases where a screw up is too expensive and researchers simply need to maintain control.

In fact, giving non-researchers the tools they need to become successful in tactical evaluative research actually increases the appreciation and value of dedicated research teams. Researchers now have the time and space to focus on strategic, high-impact research that only they can deliver. They can also continue to play the facilitator role -- providing support, mentorship, and expertise to non-researchers to help make sure that independent research within the company doesn't go off-track.

Speaking of independence, at Reduct we've built a collaborative tool that enables your team to synthesize and collaborate on qualitative research. Reduct allows anyone to organize long hours of UX research videos into themes, and present them quickly to stakeholders through shareable reels that we and many of our customers like to call "research snacks". By stitching the transcript of a video with the audio, we enable highlighting, clipping and synthesizing insights from video in a way that"s never been done before, as easy as editing a Google Doc.

![[Advancing Research 2022] What Design Research can learn from Documentary Filmmaking](/static/a0a907b113aa60d7720b84b21e85dbaa/06771/documentary-film-meets-design-research.webp)