Tags, Tagging, & Taxonomies

March 2023

·

6 min read

Structure and meaning

There are as many taxonomies and approaches to tagging as there are organizations, researchers, and research studies. There’s a deep well of approaches on how to think about tags in fields as diverse as the humanities (especially anthropology and sociology) and library and information sciences.

Tags are often used to analyze qualitative data such as interview transcripts, helping researchers to connect the dots thematically, either within a single interview across a set of interviews that make up a research study. They can also serve as a primary metadata type, to bring some structure to a repository or an archive. Tags are an integral part of Reduct, with powerful and flexible tools to let you work however you work best, whatever your use-case.

Broadly speaking, there are two main approaches to coding qualitative data, such as interview transcripts: A priori coding, where a set of tags or a fully fledged taxonomy is determined before interviews begin or before data is analyzed, and inductive coding, where tags are developed by the researcher or team of researchers as a result of the analysis itself. In-vivo coding is a variant of inductive coding, where the words used by research participants are themselves used as tags. Qualitative researchers often talk about "grounded theory", with tags, ideas, and concepts “emerging” from (and “grounded in”) the data, and later sorted and grouped.

In practice, particularly in commercial or corporate environments, researchers land somewhere between these two methodological extremes: they have a hypothesis going into the fieldwork, and establish a number of tags beforehand to represent topics that are expected to be covered in the interviews, but these evolve and are added to as interviews take place and the synthesis process runs its course. The exact balance varies, depending on the organizational context, study aims, and researchers’ methodological background, experience, and instincts.

In some organizations with established ResearchOps or knowledge management practices, there may be enterprise-wide taxonomies that all projects must adhere to; more commonly, there are a set of tags that are augmented on a project-by-project basis. In other cases, researchers might start each study or project with a blank slate, with the flexibility to determine the appropriate tags for that study in isolation.

Immediate value, value over time

Tags and taxonomies can provide value at three distinct time-horizons, each requiring a different mindset:

-

Short-term use - to help a user pull together the right clips from one or two recordings which may have covered a range of topics; this activity is usually individual in nature.

-

Medium-term use - to support and enable an individual or a team to analyze a series of interviews across a study, and to identify themes and connect the dots between recordings.

-

Long-term use - A shared taxonomy can unlock longitudinal value of a research repository, helping users uncover insights from research conducted months or years prior, and will often stretch across organizational silos.

When a taxonomy is intended to provide value over time, and especially when it is used by a large group of people, it is often worth carving out time or assigning resources to manage the taxonomy — removing unused tags, merging those that are rarely used and similar in meaning, and adding synonyms to avoid confusion, duplication, and fragmentation. These tasks become particularly important when determining which portions of a taxonomy should scale and be shared across projects and departments, and which should be considered temporary and study-specific.

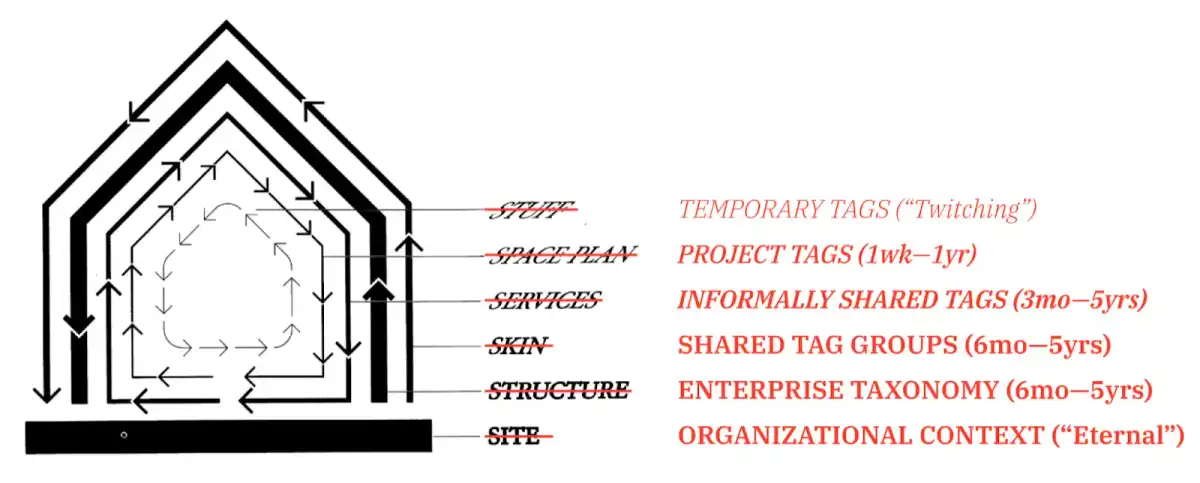

These time-horizons might also be thought of as pace layers, in the tradition of Frank Duffy and Stewart Brand. For example, a shared taxonomy intended to be used across a large organization (equivalent to "the site") changes slowly (over the course of months or years), a set of tags intended to be used by a defined team for a specific project will evolve over the course of the project (weeks-months); tags used for a single recording or when quickly assembling a reel might be considered throwaway, or to be “twitching” over days or a handful of weeks.

These layers are not all required: not all organizations have (or need) enterprise-wide taxonomies; a quick-and-dirty reel might not need the structure and rigor of tag groups built to support the collaboration of a project team. But where you do have more than one layer, it can be helpful to conceptualize them as distinct-but-related, and always informing each other: if you’re repeatedly creating a tag or a set of tags (or even tags that are slightly different but conceptually related or adjacent) for multiple projects, perhaps they should be integrated into a slower layer, and if a tag in a shared structure is never used, it may be better to retire it. As Stewart Brand puts it, "The fast layers innovate; the slow layers stabilize. The whole combines learning with continuity."

Working with tags in Reduct

You can tag highlights in a recording, or elsewhere in the app, offering the flexibility to adjust your workflow as needed. You can use any combination of the following:

-

You can highlight and tag directly in the context of a recording.

-

You can view highlights in a list view (all highlights in a project, or filtered to a recording, by highlighter, or previously applied tags), and add tags.

-

You can bring highlights into a videoboard, where you can arrange them spatially, use frameworks to structure your synthesis, and add tags to individual highlights or to a selection of several.

A team might have a workflow on a study that involves creating highlights on recordings as they are uploaded or imported, and applying two or three high-level tags in context. Later on, more granular tags can be applied in either the list view or using the videoboard, as a precursor to creating reels or integrating clips into your output. As an example, a first tagging pass through a document might just tag relevant highlights with "color," (along with other tags at a similar level of abstraction, perhaps “shapes” and “texture”), with a secondary pass applying “red,” “yellow,” and “blue” as appropriate.

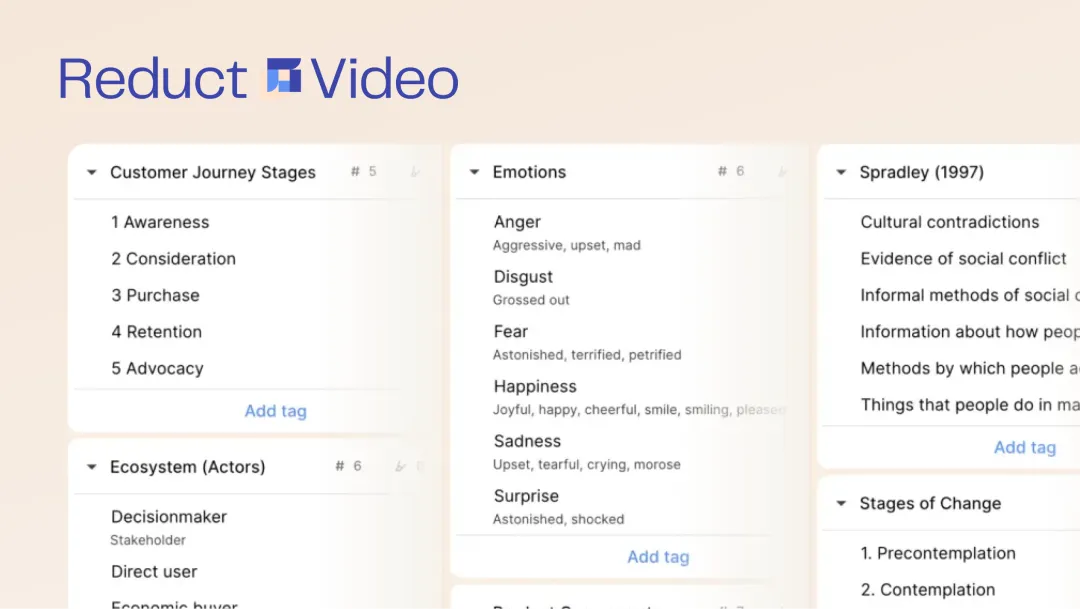

Reduct allows you to create tags in-context, anywhere you can add a tag to a highlight, as well as when the left sidebar is displaying your tag codebook. There you can create tag groups to add some hierarchy to your tags, and rapidly find the right tags using the quick-filter. It’s here that you can also manage your tags and emerging (and/or sprawling) taxonomy: drag-and-drop tags into groups, rename tags or groups, and merge tags and groups, as needed.

You can also add a description to a tag. This can make a taxonomy more approachable, graspable, and usable by individuals who were not involved in any discussions about how best to represent ideas in each tag. The description field can also document synonyms to help keep a taxonomy from fragmenting. For example, a tag about the color "red" might have in its description “burgundy, rouge, crimson, ruby” to indicate that clips related to any of these shades should use the “red” tag despite their nuanced differences. This is unavoidably a judgment call about which nuances are worth capturing in individual tags or combining into a single one: a company specializing in lipstick might care about different shades of red to a different extent to an organization studying the use of children’s toys.

When tagging a highlight, the autocomplete matches tag group names, tag names, and this description field. So if we imagine that the "red" tag (with synonyms listed as above) is in the group “colors,” you could type “color”, “red”, or “crimson” to rapidly find and add that tag to your highlight.

To dive deeper into this illustrative example and read some tips on how to set up your tags and tag groups, take a look at "A Close Read of a Tag Group."

Taxonomies in action

Creating tags or a whole taxonomy for a project, or even for long term use across an organization, can be a major undertaking, and involve a variety of judgment calls and balancing acts. You’ll want to make sure that your tags and tag groups are calibrated to the content they will be applied to, and to the work they are intended to support. Too general, and you’ll lack the structure tags are supposed to bring to the table; too specific, and you’ll have many tags, each only applying to a small number of highlights, with the total number overwhelming users in the project.

It can be tempting to foresee everything that might come up in your material - but attempting to do so will only guarantee that you’ll both end up with a very large number of tags, and there will almost certainly be something missing (Borges’ "Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge" notwithstanding). Evaluative research will necessarily have less unknowns than generative discovery research, but even when the research is highly structured, things may turn up during the analysis that you weren’t planning for, which you may want to tag. In many situations, it can be helpful to set up a handful neatly grouped tags for topics that are predictable and expected, and allow other themes to emerge from the process (and making sure to plan in time to clean things up along the way); the balance between these will vary depending on the type of research you are conducting, the nature of your team, your own instincts and style, and the timeline and constraints you are working within. In other words: don’t stress! Plan ahead not by trying to predict the future, but by leaving time to adjust your structure to embrace the unexpected.