As Audiovisual Evidence Mounts, Public Defenders Struggle to Keep Up

September 2025

·

5 min read

The widespread use of smartphones, surveillance cameras, body-worn cameras and other digital devices has led to a massive increase in the creation and storage of audiovisual evidence.

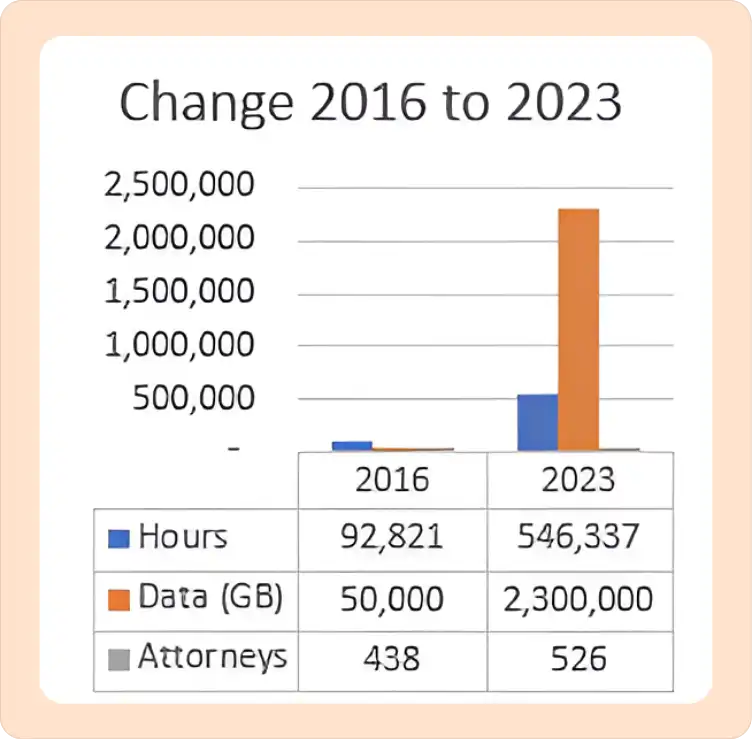

Since 2016, the amount of digital evidence in the Office of the State Public Defender (OSPD) is receiving and storing in its cases has increased a staggering 4500%. This surge in digital evidence is pushing public defenders (PDs) to the brink.

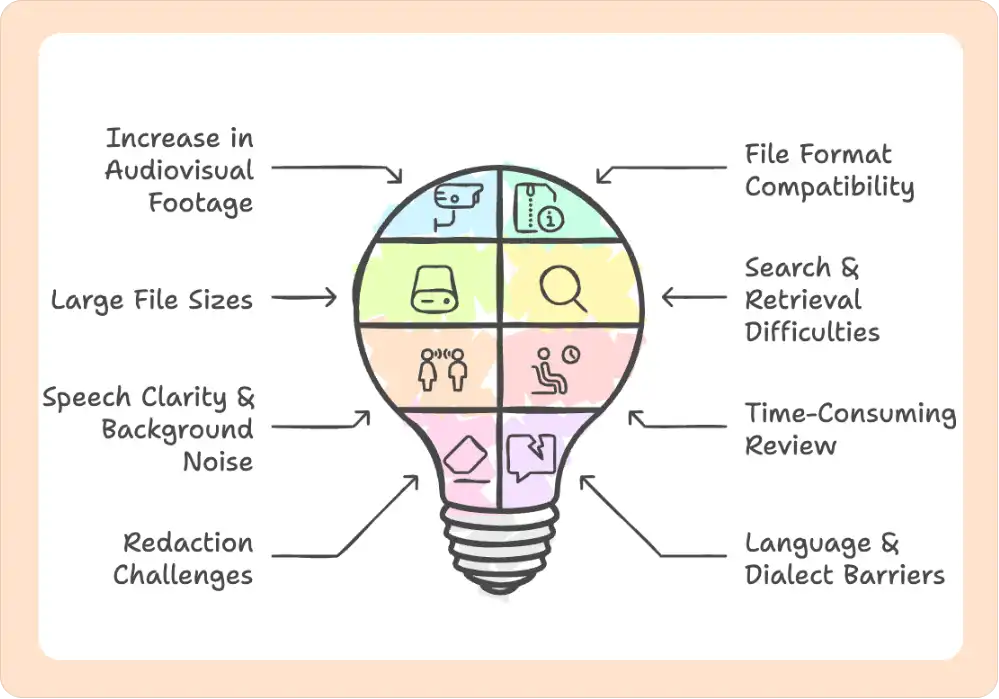

Just like any other type of evidence, working with audiovisual evidence comes with its own set of challenges. Knowing how to navigate these difficult waters can be the key to ensuring a fair trial or risking an unjust outcome.

Current processes are patchy at best.

Attorneys read police reports to pinpoint where to focus, manually acquire data from multiple sources, and then cross-reference every second of the audiovisual evidence to uncover key evidentiary details.

They then spend an overwhelming amount of time manually reviewing the audiovisual evidence. It’s a tedious, time-consuming process and adds extra steps that force PDs to work 60 to 80 hours a week.

The workload is not only straining their ability to defend clients but also contributing to high turnover in state public defender offices.

Why is managing audiovisual evidence challenging?

Too much footage, too little time

A study conducted by IBM, estimates that 90% of all the legal cases now involve some form of audiovisual evidence.

A decade ago, public defenders dealt with a handful of grainy surveillance clips or a single witness interview recording.

Fast forward to today, every case comes with a deluge of footage—Zoom depositions, cell phone recordings, CCTV clips, body-worn cam footage, and more. The sheer volume of audiovisual evidence is increasing with the case, and it’s not slowing down.

For instance, felony cases can include up to 200 hours of video footage, making it nearly impossible for defenders to thoroughly analyze all the relevant material.

This systemic challenge is impacting both the efficiency and effectiveness of public defense.

Lack of storage for large files received as discovery**

High-resolution video and audio files are great for clarity, but they come with a cost: massive file sizes.

A single body-worn cam video can easily be several gigabytes, and when you’re dealing with multiple cases, the storage requirements add up quickly.

The Oakland, Calif., Police Department, which currently has 600 Body-worn cams deployed, retains video for a remarkable five years.

As a result, storage needs have increased significantly over the past couple of years and the department now captures on average almost 7 TB of video data per month.

Whereas, other departments store over 100,000 hours of footage annually, further highlighting the scale of the issue.

Storing massive amounts of high-resolution audiovisual evidence requires significant storage capacity– this resource can be expensive and difficult to maintain.

With limited resources, PDs are hard-pressed to comb through terabytes of data including hundreds of hours of jail calls and thousands of hours of body-worn cam recordings.

To make matters worse, finding a single case file in this mountain of data is like searching for a specific grain of sand on a beach.

As files pile up and storage systems struggle under the weight, finding a specific case and organizing its audiovisual evidence becomes a tedious bottleneck—further delaying justice in an already overburdened system.

Recovering relevant footage from multiple sources

A 2016 report by the National Institute of Justice found that law enforcement agencies had access to 66 different body-worn camera models from 38 vendors, each with its own file format and playback requirements.

Different devices—smartphones, body-worn cams, surveillance systems record in different formats such as DAV files from CCTV systems or G64 files from Genetec surveillance.

Some files might play perfectly on one platform but be unreadable on another.

This means public defenders often need to juggle multiple software solutions—like VLC Media Player, QuickTime, or Dahua Video Converter just to open and view evidence.

Blurring out bystanders’ faces accidentally caught on footage

Redaction is a critical step in preparing audiovisual evidence for court, but it’s far from simple.

Manually blurring faces, bleeping out names, or masking sensitive information whether it’s private details accidentally revealed in a screen share or bystanders caught on camera is a tedious and time-consuming headache.

While redacting the audiovisual evidence, if you remove too much, you risk weakening the evidence. If you remove too little, you could violate privacy laws or expose sensitive details.

Adding to the complexity, a 2022 study titled "Story Beyond the Eye: Glyph Positions Break PDF Text Redaction" found that many redaction tools don’t fully erase blurred details in PDFs or clips.

Even after a portion is masked, character positioning clues can still be reversed, undermining the entire redaction effort.

Most redaction tools require technical expertise, and some don’t even provide secure redaction, leaving room for errors or breaches.

For public defenders, who are already stretched thin, this becomes a bottleneck.

The hidden costs of poor audio quality

Poor audio quality is the bane of any legal professional’s existence.

Muffled voices, overlapping conversations, and background noise—common in incidents like street altercations or crowded arrests can turn a critical piece of evidence into an indecipherable mess.

Transcribing body-worn cam footage from chaotic scenes like protests or crime scenes, where audio quality is poor, takes significantly more time compared to clear, good-quality audio from a controlled environment, like an interview room.

Basic video editing tools often struggle with low-quality audio, and some automated transcription services can have error rates as high as 10-20% in noisy environments.

Similarly, identifying multiple speakers, especially in recordings with overlapping dialogue or poor audio quality, poses another challenge that leads to misinterpretations.

As a result, public defenders spend an average of 10-15 hours per case cleaning up and transcribing poor-quality audio evidence.

Digging through the digital haystack: finding relevant clips

Imagine trying to find a specific 30-second clip in a 10-hour recording. Without a proper search feature, tagging, transcription, or metadata, it’s like searching for a needle in a haystack.

Public defenders don’t have the luxury of time to watch every minute of footage.

They need tools that allow them to quickly locate relevant moments of their clients in the crime scene, and most of the tools lack the access to advanced search functionalities.

Overload of audiovisual evidence in a single case = unstructured data. This makes it nearly impossible to pinpoint a specific moment.

Keeping sensitive footage out of the wrong hands

Audiovisual evidence contains highly sensitive information—victim statements, confidential informants, or private conversations.

For public defenders, ensuring these data remain secure is non-negotiable.

But here’s the catch: you also need to make it accessible to the right people at the right time. This balancing act is tricky.

You’re dealing with multiple stakeholders like lawyers, paralegals, expert witnesses and each needs access without compromising the integrity of the evidence.

Add to that the risk of leaks or unauthorized access, and you’ve got a recipe for sleepless nights. It’s like guarding a vault while still needing to open it frequently—you need a system that’s both secure and user-friendly.

The audiovisual evidence overload isn’t going away. Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach.

Investment in modern tools—such as AI-powered transcription, automated redaction tools, and unified platforms for evidence management can help public defenders manage their caseloads.

With the right tools, PDs can turn this challenge into an opportunity. If you’re tired of drowning in footage and ready to take control of your audiovisual evidence, it’s time to embrace a new way of working.